Pouch & Bandolier

| Beading and Designs by David Mott and in 19th Century Seminole Men`s Clothing

|

Pouch & Bandolier

| Beading and Designs by David Mott and in 19th Century Seminole Men`s Clothing

|

The beading technique is the two-needle, or two-thread, applique

method. The most common bead size used is equivalent to our current

12/0 size. Native American crafters weren't necessarily consistent

on bead sizes within a single piece, but the range is still within

11/0 and 13/0. This style of beading is simple, and certainly

does not require a loom.

Older opaque colors are to be preferred; in darker colors, sometimes

transparents and infrequently cuts. Look for dull white instead

of bright white, salmon or rose instead of pink, greasy yellow

or mustard instead of yellow or gold, crimson or wine red instead

of bright red, and dark blue instead of royal blue. Light blue

is pastel, and turquoise is not bright. A good Indian hobbyist

catalog will carry these, and if you have to spend a little extra

to get the old style colors, it will be well worth it.

The colors should contrast with the strouding color and with each

other. (See Appendix *1) COLORS, for an idea of how few colors

were usually used on a single item.)

A distinction between Seminole

and Creek or Cherokee pouches and bandoliers is that the elements

in a Seminole repeating design are much less likely to be connecting

in a rolling repeating curve. In fact, many Seminole designs are

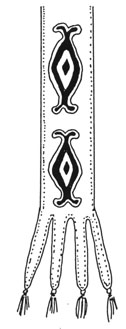

isolated elements, not linearly connected at all. Most pouches

had designs that coordinated with those on the attached bandolier.

The pouch design is usually (but not always) bilaterally symmetrical.

That is, like people, the left half is a rough mirror image of

the right half. The whole flap was often fully beaded. The pouch

was not beaded on the back and not always filled in completely

where the flap lay over the front of it, but the front side could

be fully beaded or partially beaded.

A distinction between Seminole

and Creek or Cherokee pouches and bandoliers is that the elements

in a Seminole repeating design are much less likely to be connecting

in a rolling repeating curve. In fact, many Seminole designs are

isolated elements, not linearly connected at all. Most pouches

had designs that coordinated with those on the attached bandolier.

The pouch design is usually (but not always) bilaterally symmetrical.

That is, like people, the left half is a rough mirror image of

the right half. The whole flap was often fully beaded. The pouch

was not beaded on the back and not always filled in completely

where the flap lay over the front of it, but the front side could

be fully beaded or partially beaded.

The bandolier is another story. The design on one half of its

length could be completely different from what's on the other

half. So, a wearer might seem to be wearing two completely different

bandoliers when seen from the front or from the back. Occasionally,

an isolated design element might appear where the two halves meet

on the shoulder. The author feels that this change may be more

from boredom in construction than from any specific intent. There

are, however, a few bandoliers with consistent design through

their whole length. No bandolier is fully headed.

The designs, especially Seminole motifs, can be repeating, geometrical

(but not with rigid straight lines or sharp corners), and representational

(but not really pictorial). This may not be so much stylistic

preference as much as required by the limitations of working with

linear strings of beads.

Here are a few patterns noted on some pouches and bandoliers.

The names have been assigned by the author for ready referral;

there is no indication at all that they were actually intended

to represent any of these.

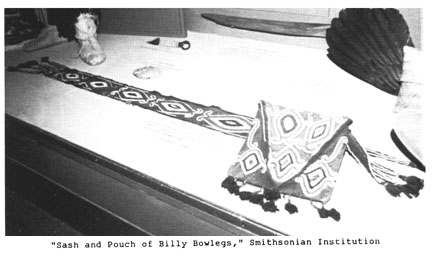

RATTLESNAKE: Appears in the bandolier of Billy Bowlegs

in his photographs and engravings, although not on the example

in the Smithsonian ascribed to him. Although the pattern strongly

resembles Seminole heddle loom beaded sashes of the late 19th

and early 20th centuries, this is definitely an applique beaded

sash.

RECURVE DIAMOND: Perhaps the most popular motif

among 19th century Seminoles. It s several variations appear on

a majority of the examples studied. That the design was enduring

Is Indicated by the fact that it appears on one made by a Seminole

in the early 1950's, commissioned by William C. Sturtevant.

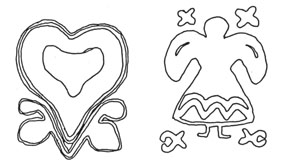

HEART: Appeared

on a pouch recent1y sold to a private collector.

HEART: Appeared

on a pouch recent1y sold to a private collector.

ANGEL: (or, female figure): Appears on several bandoliers.

It seems appropriate, in that it was women who made the pouches

and bandoliers.

MAN: On a single example.

SWASTIKA: A familiar motif throughout all of Native

American art. Note, however, the direction of rotation. The opposite

direction represented bad luck or misfortune.

FLORAL: In Seminole examples, this is mostly limited

to leaves. More fully floral beadwork is more typical of Creek

or Cherokee examples. A mixture of floral and diamond is on Cat1ln's

painting of Osceola (although we should be cautious of Catlln's

details.)

Sketch out your chosen motifs, and mark the outlines on your strouding.

An option is to draw the design on regular writing paper. Lay

the paper on the wool, and sew the first outline string of beads

down onto the wool through the paper. When the outline is sewn

down, the paper can easily be separated and the rest of the beadwork

filled in with the outline.

But, given the usually irregular, uneven appearance of elements

in Seminole designs, it is highly unlikely that they used either

drawn or paper outlines. They probably started out with an idea

of what they wanted, possibly with a rough sketch off to the side,

and did the whole thing freehand. Perfectly repeated patterns,

or even very straight lines, are not to be expected in Seminole

pouches and bandoliers.

ORDER ENOUGH BEADS FOR YOUR PROJECT… size 12/0 beads

are very small, so one or two hanks is hardly enough for the project.

Ten to fifteen hanks can easily be used on the bandolier alone.

Figure each hank can cover about four to five square inches of

solid beadwork.

Remember, also, to order thread and needles that match your bead

size. The author recommends #13 needles and extra fine or FF thread.

Some beeswax needs to be on hand to wax the thread periodically.

One source does discourage thread waxing because they feel that

it might discolor the wool.

If this is your first try at any kind of beading, it's recommended

that you start with a simple motif on the bandolier.

Cut the beads off of a hank into a shallow saucer or small plate.

A Frisbee works finer For storage, 16mm film canisters or old

cellophane tape cans have lids that can be closed tight. Wax a

yard of thread to hold the beads. Pull the thread through the

needle until the needle is in the middle of the length of thread.

Knot the two ends together with three passes of an overhand knot.

Run the thread through the wool with the knot on the outside of

it, the side of the wool the beads will be appliqued onto. Pass

the needle back through the wool again, close to the starting

knot, so the thread_is again on the outside.

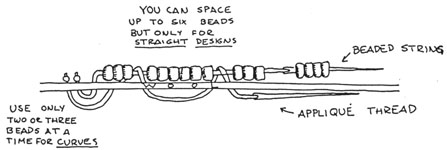

An easy way to string the desired beads is to run the needle through

the loose beads in a scooping motion. Or, you can slowly and tediously

put one bead at a time on the needle. Repeat until you've accumulated

a long string of beads. Cut another yard of thread, wax it, but

keep this thread as a single strand. Start it out close to the

stringed beads, with the knot also on the outside. Cross over

the bead thread, tacking it down every few beads to the fabric.

You are not sewing down the beads, you are sewing down the thread

that carries the beads. Keep both the beads on the thread and

your tacking stitches drawn tight. The beads between each tack

would be more on a straight run, such as four or five, and less

on curves, perhaps two or three between each stitch. If the beads

and stitches are loose, the beads will sag. If the beads and stitching

is too tight, the completed beaded pattern will bulge up. Different

tensions will be called for different kinds of lines. Check periodically

to see if all is well on the underside of the wool.

Eventually, either the bead thread or the applique thread will

begin to run out, or you will finish with this particular bead

colon If the applique thread runs out...

Make two or three passes over the last stitch in front of the

last bead. Run the applique thread through to the wool's underside,

and run the thread through these last few stitches, passing the

needle through the loop you create. If there are other beads to

add, start threads as before, and finish.

If the bead thread runs out shy of completing the motif, or if

you are finished with one color and want to start another...

Pull the beads tight, and enter the wool with the needle without

breaking the surface, and run the needle through the created loop.

Again, do this at least twice over.

Remember to keep all your beadwork relatively tight, as needed.

Take your time. Set the project aside when you get tired. You

may want to work at it in stages, setting a goal to complete a

part of the design or a particular color at a sitting.

Seminole Bandolier Attachment & Conclusions

Appendix & References for Seminole Pouches & Bandoliers

Return to the Introduction to Seminole Pouches & Bandoliers

Complete Index to Articles in 19th Century Seminole Mens Clothing

|

Text and Graphics

© 1994 - Tara Prindle unless otherwise cited. |