iswi-baakwa-togan An Ojibwe/Metis Account of

by Pierre Girard

|

Making Maple Sugar at Mille Lac, Minnesota (Densmore 1979) |

iswi-baakwa-togan An Ojibwe/Metis Account of

by Pierre Girard

|

Making Maple Sugar at Mille Lac, Minnesota (Densmore 1979) |

It is that time of year again. Nights are cold and days are warm and the sap is running. For the Ojibwe this was always a time of renewal. Family groups reunited with their band and relations and friends who'd not seen each other over the winter could gather for the work of sugaring which seemed more like a festival than work.

Cakes of Maple Sugar and Makuk Filled with the Same (Densmore 1974) |

Boiling the sap down in an old copper corn boiler kept one of us constantly feeding the fire or stirring the boiling sap to keep it from burning as it became syrup. Forty gallons of sap were needed to make one gallon of syrup. Making the syrup into sugar required even further evaporation, though we only went as far as hardening the syrup by dropping the hot syrup into the snow. Put up this way it is known as "wax sugar."

Birch Bark Containers (Densmore 1974) |

I'd picked out a sugar bush close to Hunter Lake last fall while hunting. It was off a trail north of us, but when I checked it two weeks ago I found the trail had been blocked and no entrance was possible. I put the idea on the back burner for a while, but yesterday as I compared night temperatures to day temperatures I realized I needed to get moving if I was going to get any sugar this year.

Stacked Dishes and Empty Cones, the Latter to be filled with Sugar (Densmore 1974) |

The first bit of a way is on a trail I'm well familiar with and there were no surprises. Eventually I left the trail and set out across a swampy "moose pasture." On the far side the land climbs through birches, balsams and aspen. This is nice high land and I have a hope of seeing some maple. After following the ridge for some time I am able to see the next low spot, more moose pasture. On the far side I can see what I am sure is a good size maple among the birches and ash trees. Crossing this moose pasture is more of a problem than the first as there seems to be a small stream in the center. I am able to cross safely but my mogasins come away a little damp.

Maple Trees Tapped (Densmore 1974) |

In the whole area there is no other maple of a size to support a tap. Everything I'd thought was a maple from a distance turns out to be an ash when I get closer. I hear noise in the brush several times, but I can not find the source of it. Everytime I look up the noise ceases. Finally I set off to the east toward higher ground. I travel for a mile or more through small aspens and larger birch. At last I come to a large network of ridges. There is much less snow here where the trees are deciduous and the sunlight is better able to make its warmth felt. Here and there I see a maple, but I am not ready to make the same mistake I'd made with the first maple. I decide to look for a real "sugar bush" where I may put out many spiles close together.

In the distance I see what looks like a good stand of maples. They are close together and appear to be just what I am looking for. When I get closer I can see that some of the trees are basswoods, but still there are many maples. When I get right up to them I can see that some do not look just right. I look at the leaves near the base of one and I am surprised to realize it is an oak. We do not have many oaks so far north. These are red oaks and look surprisingly like a maple this time of year, at least from a distance. Still, there are enough maples and I drill and tap three large trees and place the sap gathering makuks. The sap begins to run as soon as I drill the holes. I could make a "V" and pound in a wood chip like the old Ojibwes, like the "gete" or old ones, but I think it would do more harm to the trees. I boil coffee over a small fire and thank the Creator for his kindness to me.

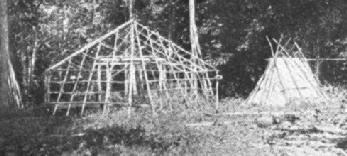

Frame of Lodge in which Maple Sap was Boiled, and Storage Lodge for Utensils (Densmore 1974) |

Storage Lodge for Sugaring Utensils (Densmore 1974) |

On the far side of this grove, looking through the birches, I see what appears to be another grove of maples further along the same ridge. This grove appears to be much larger and I head toward it.

Following the ridge I can see a well worn game trail, wherever it peeks though the snow, and plenty of deer sign, though none immediately fresh until I've gone a little ways. There I see where a young deer has come onto the trail from the south. Other tracks, also new, are over the deer tracks in spots. I can see they were made within the hour, because the sun has not bothered them yet. They are not chasing the deer, just following it. I cast about and locate two other sets of tracks. They appear to be timber wolves, Mainga. One set of tracks is very large. The other two would be normal for any mid-size dog. The warm fur filled piles of wolf scat clinches it. Not dogs. As always I feel the hair raise on the back of my neck. I know the wolf is the friend of the Ojibwe, but I am just a little bit Ojibwe, probably not enough for the wolf to recognize.

I enjoy living in an area that can support loons, Canada jays, eagles and wolves, for their presence means I am still in the wilderness, and I am only aware of one wolf attack on a human recently (and that seems to have been a mistake), but I've watched them kill deer and it was done so fast and efficiently that I have little doubt several of them together could kill me if they decided to. In the morning I will bring the children here. I resolve to bring my gun with, just to have something more to carry, in the morning.

Boiling Maple Sap (Densmore 1974) |

Heading due south I find myself cutting across my outgoing trail sooner than I expected. It is amazing how many things hide in the forest. Twelve years I've lived at Hunter Lake, hunting and snowshoeing these woods, but I never suspected such fine maple ridges so close by.

Had a good time today. Like those old Ojibwe, I'm tired of the winter; I'm ready for the spring. It was a good day, today, to be alive in the great north woods!

We later put out 15 more spiles. We have got an amazing amount of sap for the few taps and little time we could devote to this. So far we have about two gallons of syrup. Not a lot, but good for a start. Next year we will do 100 taps.

Gi-ga-wa-ba-mim-ba-ma

(see you later)

Pierre Girard

(AKA Bemosi Mukwa or Walking Bear)

Image credits: Photographic images scanned from the works of Frances Densmore in the early 1900s:

1974 How Indians Use Wild Plants for Food, Medicine & Crafts. Dover Publications, New York. First published in 1926-1927 by the Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology as 44th Annual Report.

1979 Chippewa Customs. Minnesota Historical Society Press, St. Paul. First published in 1929 by the Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology as Bulletin 86.

Web Design & Graphics © 1994 - 2002 Tara Prindle.