| Shell beads have long had cultural significance to the Native Americans of southern New England; shell beads in the Northeast have been found which are 4500 years old. These shell beads were larger and relatively uncommon because drilling the material was difficult with stone drill bits. This earlier bead, proto-wampum, was traded within ceremonial contexts, in part for the connections of shell with water and its life giving properties. |

| Shell beads come in many traditional shapes and sizes, including small discs or hishi beads. Before contact with Europeans, shell beads were either disk shaped, or barrel shaped, usually made from the whelk's spiraling inner columnela. Other shapes of shell beads include tubes, and other forms resembling a ball, cone, diamond, square, or hourglass. |

The word "Wampum" comes from the Narragansett

word for 'white shell beads'. Wampum beads are made in two colors:

white ("Wòmpi") beads ("Wompam") from the Whelk shell ("Meteaûhock"),

and purple-black ("Súki") beads ("Suckáuhock")

from the growth rings of the Quahog shell ("Suckauanaûsuck").

There are several types of Whelk used to make the white beads and pendants

with the Latin name 'Busycon'. In southern New England beads are often

manufactured from two local species: Busycon canaliculatum

(Channeled Whelk) and Busycon carica (Knobbed Whelk), which both inhabit

the waters from Cape

Cod southwards to Florida. Early historic Iroquois wampum also originates

from the species Busycon sinistrum (Lightening Whelk) along the coast from New Jersy

through Florida around through the Gulf, and also from the species Busycon

Laeostomum (Snow Whelk) who's habitat ranges from New Jersy down to Virginia

(Pendergast 1983: 97-112).

Some early historic documents contain innacurate references

to the shells being of periwinkle or muscle shell, sometimes

mistaking the beads themselves for porcelain or bone. The periwinkle shell

was not even introduced to the New England coastline until the late 1800's

(Krepcio 2001: personal communication).

Wampum from Middle and Late Woodland

periods (beginning around AD 200) had a robust shape, about 8mm

in length and 5mm in diameter, with larger stonebored holes

of more than 2mm. Wampum beads of the mid-1600's average 5mm

length and 4mm diameter with tiny holes were bored with European

metal awls average 1mm. Seneca's in New York after European contact

during the late 1600's had increasing numbers of shell beads which

measured approximately 7mm length and 5mm diameter, having metaldrilled

holes with a diameter of just under 2mm.

Wampum from Middle and Late Woodland

periods (beginning around AD 200) had a robust shape, about 8mm

in length and 5mm in diameter, with larger stonebored holes

of more than 2mm. Wampum beads of the mid-1600's average 5mm

length and 4mm diameter with tiny holes were bored with European

metal awls average 1mm. Seneca's in New York after European contact

during the late 1600's had increasing numbers of shell beads which

measured approximately 7mm length and 5mm diameter, having metaldrilled

holes with a diameter of just under 2mm.

The quahog shell used to produce purple wampum and other shell pendants

is exclusively the species with the Latin name 'Mercinaria mercinaria'

The quahog shell used to produce purple wampum and other shell pendants

is exclusively the species with the Latin name 'Mercinaria mercinaria'

European traders and politicians, using beads and trinkets, often exploited gift exchange to gain Native American favor or territory. With the scarcity of metal coins in New England, Wampum quickly evolved into a formal currency after European/Native contact, it's production greatly facilitated by slender European metal drill bits. Wampum was mass produced in coastal southern New England. The Narragansetts and Pequots monopolized the manufacture and exchange of wampum in this area.

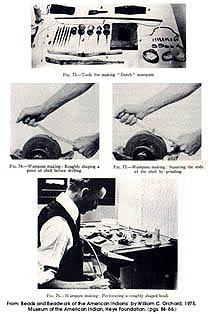

Tools for making "Dutch" wampum (Orhard 1975: 84). Click for closer view. |

The intense hardness and brittleness of the materials made it impossible to wear, grind, and bore the shell by machinery alone. First the thin portions were removed with a light sharp hammer, and the remainder was clamped in a scissure sawed in a slender stick, and was then ground into an octagonal figure, an inch in length and half and inch in diameter. This piece being ready for boring was inserted into another piece of wood, sawed like the first stick, which was firmly fastened to a bench, a weight being so adjusted that it caused the scissure to grip the shell and to hold it securely.

The drill was made from an untempered handsaw, ground into proper shape and tempered in the flame of a candle. Braced against a steel plate on the operator's chest and nicely adjusted to the center of the shell, the drill was rotated by means of the common hand-bow. To clean the aperture, the drill was dexterously withdrawn while in motion, and was cleared by the thumb and finger of the particles of shell. From a vessel hanging over the closely clamped shell drops of water fell on the drill to cool it, for particular care was exercised lest the shell break from the heat caused by friction (Jennings 1976: 93-94).

A fathom (six feet of strung beads) of white wampum was worth ten shillings and double that for purple beads. A coat and Buskins "set thick with these Beads in pleasant wild works and a broad Belt of the same (Josselyn 1988: 101)" belonging to King Philip (Wampanoag) was valued at Twenty pounds. Even in the 1600s there was noted distinctiveness of Native-made wampum and the inability of others to counterfeit it, although attempts at imitations included beads of stone and other materials.

|

|

| King Philip, Wampanoag [from a lithograph

by T. Sinclair appeared in Events in Indian History, 1842].

|

"Strung money was known as wampumpeage, or merely peage. Customarily arranged in lengths of one fathom (6 feet), which contained anywhere from 240 to 360 individual beads, depending not only on the size of the beads but on their current worth, for "fathom" soon came to denote a specific monetary value. Individual strands were then worked into bands from one to five inches wide, to be worn on the wrist, waist, or over the shoulder, ... Occasionally the Indians fashioned great belts containing over ten thousand beads" (Vaughan 1979: 120 124).

With the increased manufacture after

European contact, these beads were carried inland along indigenous

trade routes as far as the Great Plains and as far south as Virginia.

By the 1700's the Dutch Europeans began to fabricate vast quantities

in factories such as the Campbell wampum factory New York.

"The use of wampum as money, even among the English, continued until the American Revolution. Important matters such as treaty agreements were likely to be marked by an exchange of Wampum belts, with designs in two colors, which thereafter served as visual reminders of the event itself, and to call to memory the arrangements agreed on" (Russel 1980: 185).

Wampum belts consist of rows of beads

woven together. Belts were made using the techniques of both

hand-held and loom-woven beadwork, often on a simple loom made

from a curved stick resembling an archer's bow. Weaving traditionally

involves stringing the beads onto twisted plant fibers, and securing

them to animal sinew or leather thong warp.

Try your hand at weaving a Virtual Wampum Belt

Inner fibers stripped from milkweed, dogbane (a close relative of milkweed), toad flax, velvet leaf, and nettle plants were twisted into fine threads. By the 1700's a multitude of Native American weaving techniques had developed for wampum belts, bracelets, necklaces and collars. By the 1700's in New England, tubular glass beads and small round pony beads were being woven into belts and bands.

|

Long, wide belts of wampum were not produced

by Native Americans until after European contact. However, the

methods and techniques used in making large wampum belts probably

developed from the ancient Native American traditions of finger-weaving.

Some of the earliest post-European contact wampum belts were worn

as collars around the neck. These early wampum collars are made

without the use of a loom, much like prehistoric finger-weaving,

with one end of the belt anchored and the other end left free

to weave the warp and weft elements on a bias (diagonal). The

very first woven wampum most likely incorporated single beads

strung onto twine while finger-weaving sashes, garters, burden-straps

or other bands. The belt weaving technique known as 'double-strand

square weave appears earlier (late 1500's and early 1600's) than

the 'single-strand square weave' technique.

Although a loom is helpful, but not necessary, the double-strand square weave technique does not require the use of metal needles, as the beads can be strung one at a time onto the two wefts and then the wefts passed under and over the next warp string. The single-strand square weave, used by most bead-workers today, probably developed in the late 1600's and early 1700's with the florescence of the Native wampum industry.

Reproduction Bias-weave wampum collar by Prindle 2003 |

Delaware family, 1653 wearing belts, bands, strings, & medallions (Trigger 1978:218). |

Personal headbands and bracelets might combine shell with glass or metal beads. Many Native American headbands and bracelets in the 1600's in southern New England incorporated squares, triangles, diagonal lines, crosses, people, animals and other geometric shapes. Belt designs might show kinship or connection with a particular group. Belts and beads validated treaties and were used to remember oral tradition. Ceremonies of dance, curing, personal sacrifice incorporate religious and ritual aspects of beads. Jewelry was also used to display many physical or social "rites of passage", and shows that a person has gone through a certain transformation in their life, like maturity or marriage. Wampum could be presented by the family of a prospective husband to the family of a potential wife, and if accepted, granted approval for the marriage.

"The young man, when he had settled

his mind upon marrying some special girl, would appoint an uncle,

or some elderly man to be his go-between. Extra dignity was lent

to the occasion by having two old men for negotiators. He would

then procure some wampum, if he were rich enough a collar or necklace,

if not, just a string. Next he would compose a message, the

main points of which would be represented by the arrangement of

white and purple beads. This message, accompanied by the mnemonic

wampum, would be forthwith entrusted to the go-between's care,

and he would go to the home of the girl's parents carrying the

wampum in a rolled-up red handkerchief or other gaudy cloth.

Here his message would be delivered, and the wampum left , to

be debated upon by the girl's family. The negotiator would depart

for a while to allow time for deliberation. Before long he would

return for an answer. Now should the girl's family have decided

negatively, the wampum would be returned to the old man, who would

deliver it to the sender. And the matter was dropped. But should

the suitor be favorably regarded, the wampum would be retained

and upon the negotiator's next visit he would be answered in the

affirmative or asked to defer a little longer. The retention

of the wampum was considered a sign of consent. It often happened

that the husband, after the wedding, would buy back the wampum"

(Speck 1976: 254-255).

Beadwork Bibliography and Books to Buy On-Line

Reproduction wampum beads are available from Waaban Aki Crafting

|

Text and Graphics

© 1994 - Tara Prindle unless otherwise cited. |